News story credit – Steven Point News, by Gene Kemmeter, Columnist

Kemmeter Column: Family waited for news about pilot

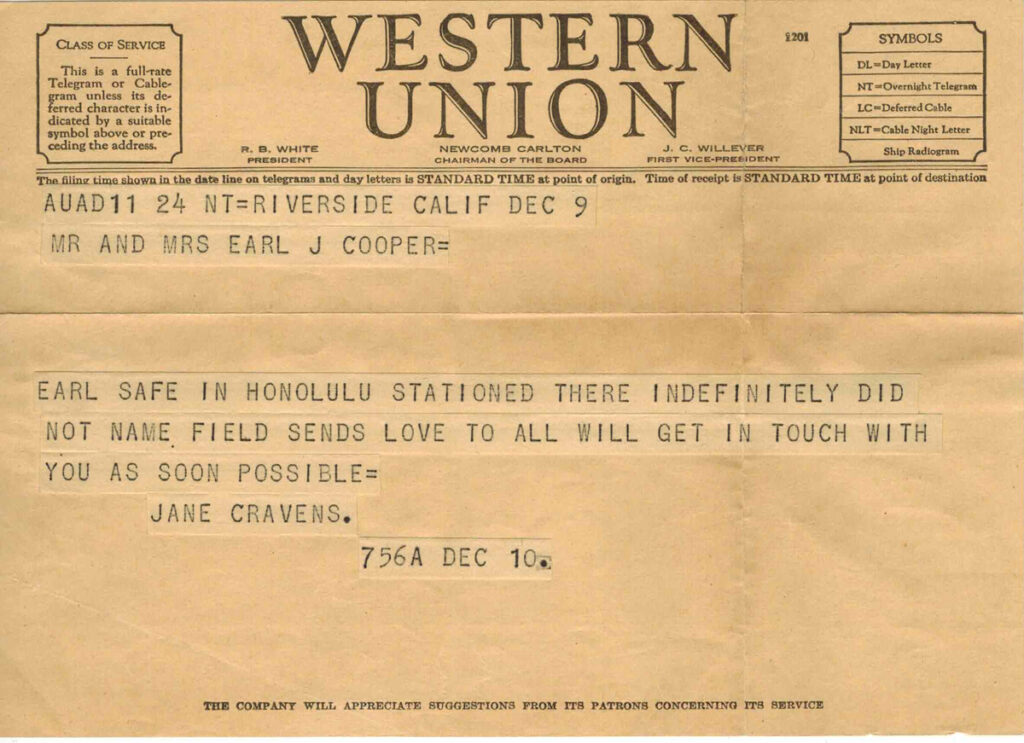

This telegram was sent to Earl S. and Lena Cooper Dec. 10, 1941, letting them know that their son, Earl J. Cooper, had safely arrived in Hawaii. Earl J. Cooper was the pilot of a B-17 bomber that flew into the Hawaiian Islands at the same time that Japanese forces were attacking Pearl Harbor.

Earl Cooper of Stevens Point had safely landed his B-17 bomber at Hickham Field after arriving in Hawaii as the Japanese were attacking Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

As he taxied down the runway, looking for a place to park the plane off to the side of the runway, Japanese fighter planes continued to strafe the airport. Cooper brought the plane to a halt, and then he and his crew exited the aircraft to find a safe place for shelter as the attack continued.

The next day, the Japanese made a surprise air attack and ground invasion in the Philippines, and the U.S. decided against sending the B-17s brought from Hamilton Field at San Francisco, Calif., to that battle station.

The situation also found U.S. forces rethinking their operations in the Pacific Theater of the war, especially with Pearl Harbor having to deal with damages to the ships stationed there and the Philippines under attack.

The attack on Pearl Harbor stunned people in America, and Cooper’s parents, Earl S. and Lena Cooper, told a Stevens Point Daily Journal reporter on Dec. 8 that their son had told them the week before he would soon be heading to Hawaii, but they had heard no word from him since then.

Two days later, the Coopers received a telegram sent from Riverside, Calif., “Earl safe in Honolulu. Stationed there indefinitely. Did not name field. Sends love to all. Will get in touch with you as soon as possible.” He later confirmed he was safe in Honolulu.

Two of the B-17s among the 12 had been damaged during their arrival and were junked. Most landed at Hickham, two landed at Haleiwa Field, a small auxiliary field for smaller aircraft on Oahu; one landed at Bellows Field; and one landed on the Kahuka Golf Course. One crewman was killed, and seven others were injured. The remaining 10 B-17s would be repaired and stationed in Hawaii to help guard the islands in case the Japanese decided to resume the attack. The planes and their crews would be patrolling to watch for Japanese ships and submarines.

The search area was a vast expanse because Hawaii is so distant from other land groups and islands in the Pacific Ocean. San Francisco is about 2,400 miles away (a 12-hour trip). The B-17s making that trip had to carry reserve gas tanks to complete the journey, yet some still ran out of fuel.

Midway Island is about a 7-1/2-hour flight from Oahu, and Midway is another 1,185 miles away from Wake Island. The planes had to island hop between locations that had landing facilities to refuel and get a meal, but little else, before taking off again. The planned trip to the Philippines included Midway; Wake; Port Moresby, New Guinea; and Darwin, Australia.

Because of the distance, pilots and crews had to carefully monitor fuel and navigation so they knew precisely where they were. Maintenance of the equipment was also important, and many aircraft had to turn back on a flight because of problems. Going down in the ocean often meant death because search planes needed to find a crew in life rafts since the planes usually sank quickly.

The patrol area off Hawaii extended to about 600 miles, a distance sufficient for a plane to spot an enemy ship and alert authorities to its location. Plane crews were working long hours. “We worked night and day, not knowing what to expect next,” Cooper said during a trip to Stevens Point in 1942. “Some of the men flew as high as 18 hours a day and are still doing it.”

On the day after Christmas, Dec. 26, 1941, Cooper and the other eight men on his plane were on patrol to the northeast of Hawaii for more than10 hours when they started to head back to Hawaii because they were running short on fuel. Cooper realized they weren’t going to make it to shore, so he decided to ditch at sea and await a rescue plane. Cooper said he performed a dead-stick landing, a maneuver that can be difficult when landing on the sea. He feathered the propellors (the dead-stick) of his plane, turning the blades into the wind, and told his crew to prepare for the crash. The plane landed on the water, allowing the crew to unload two rafts, some military Very flares and a couple of containers of three-week-old coffee. Between the crew members, they also had $600, but no place to spend it. The two rafts were each designed for two people, but all nine members got in, the four heaviest in one raft and the five lightest in the second. “It was crowded,” Cooper said, “but not too uncomfortable.”

After they got out of the plane, the aircraft, with its 35,000 pounds empty-weight, sank, and the nine men were alone somewhere in the ocean. Cooper later recalled in a March 15, 1942 speech at P.J. Jacobs High School in Stevens Point that the next morning a plane passed over, “but the pilot didn’t see us. We shot flares, but he didn’t see them. We yelled nice things – he didn’t hear them. So, we started to swear.” The plane continued on.

That first day the ocean was calm, Cooper said, but things changed that night when the waves increased in size. “The radioman and I became seasick,” he said. “We blindfolded ourselves and, as long as we couldn’t see, we were all right. But when the waves knocked us from the rafts, we couldn’t see to get back to the boat. So, then we just closed our eyes, opening them when we were washed from the rafts.”

The second morning, another plane flew over, and the crew shot some more flares, but the pilot again apparently didn’t notice them, Cooper said. Later, another plane came near, but again didn’t notice the rafts in the water. That night, he said, sharks played around the life rafts.

The waves were high again on the third morning, about 30 to 40 feet high, Cooper said, and the crew again saw a plane in the morning and then another one later in the day. About 3:30 that afternoon, he said, the group saw a flock of birds overhead and figured they were near land. The birds came near the rafts, Cooper said, and, all of a sudden, the radio operator (Pvt. D.C. McCord Jr. of St. Louis, Mo.) whipped out his .45-caliber pistol and shot one down. The bird landed in one of the rafts. “We ate the bird (raw),” Cooper said. “There was a fish in the stomach of the bird (apparently an albatross). We ate that too. In the evening the men felt better.”

The life rafts kept drifting, and on the fourth day, at 12:45 p.m., the crew spotted another plane. By that time, there was just one canteen full of water left. The crew fired more flares, and this time someone spotted the smoke from the flares.

The pilot decided to come down and take a look, so the plane circled low. The plane dropped a parcel of food that landed within 50 feet of Cooper’s crew. Then the pilot flew away.